The original interview ( here ) is translated into English by Euromaidan Press

Article by: Olha Lvova, founder of the Initiative for Think Tank Development and Research “think twice UA”

Ukraine has had three opportunities, but has not seized any of them. Today, Ukraine has returned to its usual mode – surviving and not living.

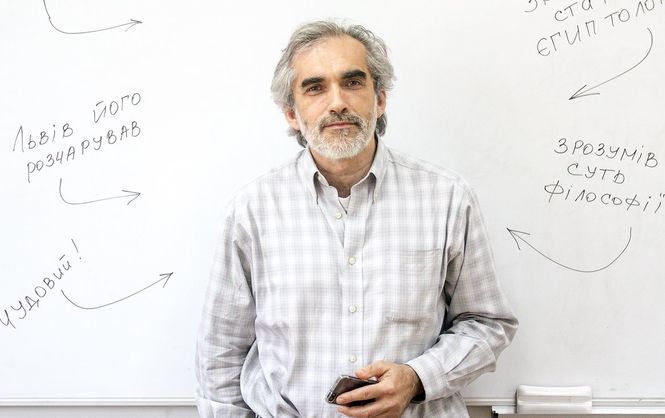

Yaroslav Hrytsak, historian and professor at the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv talks about what should be done: reforms, Ukraine’s potential, the new generation, populism, European values, UCU, etc.

Yaroslav Hrytsak expresses hope for a brighter future, asserting that a new class of people has emerged in Ukraine – about 10% of the population – people that have different values and are the key agents of change. But, he worries about which group of people will win out in the end – the smaller active group, which can move the country forward and transform it, or the more traditional and conservative one, which can set it back by decades. Hrytsak does not have the answers to this question, but believes that the active minority group will triumph.

Olga Lvova (O.L.): How do you assess Ukraine’s intellectual capital? On the one hand, we see problematic aspects; on the other – prospective horizons.

Yaroslav Hrytsak (Y.H.):

There’s no single answer because it depends on which intellectual capital you mean. If we talk about general education, Ukrainians are one of the most educated peoples in the world (at the secondary and higher education level and generally speaking, of course). I’d say that Ukraine’s highest potential lies in natural and technical sciences, but when it comes to the humanities, the potential is not the best; it’s rather low.

O.L: In this context, what you think of Ukrainian think tanks?

Y.H: There are structural problems in the academic field. Maidan hasn’t got to them yet! Let’s say that the Academy exists separately from the university; they’re two separate structures, and that says a lot about us. Because ultimately it means that Ukrainian universities aren’t really academic institutions, but teaching centres only. And if we look at the quality of teaching we can’t even call them teaching centres but more like simple schools.

The challenges faced by Ukraine require intelligent solutions: we need to identify the problem and find ways to solve it. This should be done by think tanks, such as RPR or the Nestor Group. Most successful Ukrainian professionals have become good at their jobs not through higher education or the Academy of Sciences, but in spite of them. This is a problem that we inherited from the Soviet Union, and must still overcome.

O.L: Having turned to the West, Ukraine is gradually integrating and “Europeanizing”. Do you think there’s a problem with values: Ukrainian values are difficult to compare to European ones.

Y.H: I was one of the people that introduced the word “values” in Ukrainian discourse, and now I have to suffer as the word “values” has become so blurred and banal that I’d like to stop using it for a time. Today, “values” refer to anything good as opposed to bad. But, values don’t belong in a moral category. They refer to what motivates us and determines much of our future development. They impose structural constraints that lead to failure or, conversely, create opportunity. I say this as a historian who deals with modern history, where the central theme is the rise of the modern world. Historians like empirical material, and one of the largest databases of such material was collected by Ronald Ingelhardt in his World Values Survey. (Inglehardt’s Evolutionary Modernization Theory argues that economic development, welfare state institutions and the long peace between major powers since 1945, are reshaping human motivations in ways that have important implications concerning gender roles, sexual norms, the role of religion, economic behaviour and the spread of democracy-Ed.). It clearly shows that values are important, but they’re not necessarily what we call “European values”.

O.L: Let’s look at the rule of law. Isn’t it a European value?

Y.H: It’s not a value, but a declaration. One of the biggest problems in the EU is that their politicians talk constantly about values, but aren’t at all ready to defend them. So, if they can’t defend them, then they’re no longer values. Values mean leaving your comfort zone, sacrificing your interests, health and sometimes even your life. How many Europeans are willing to sacrifice their monthly paycheck for the rule of law, never mind their lives?

Ingelhardt discusses two types of values. The first are secular and religious values that can be evaluated quite easily – How often do you go to church, the synagogue or the mosque? Is God important to you? So, what do we see? That Europe is becoming more and more secular. We see that most priests in France are 70 years old, and there will soon be no nuns in Austria and they’ll have to be imported from Africa. This high level of secularization is the result of industrialization and urbanization when masses of peasants went to work and live in cities and seemingly lost their faith. This is 19th and 20th century history. Ukraine and Russia are similar to European countries in this respect. Just look at the high rate of abortion or divorce. Although Putin puffs up his cheeks and speaks of “spiritual bonds”, it’s just blowing smoke. Our communist past has also contributed to our high level of secularization.

Religious and secular values may have some influence on reforms, but they’re not very significant. Much more important are values linked to survival and self-expression. What is more important to you – bread or your rights? Once a large group of people with post-material values appears in a country, you should expect change. These values grow as the country moves from the industrial era to the post-industrial period. It began in the 1970s and 1980s in the West, but Ukraine is still at “zero”. You know, the fact that a large number of people with post-material values appeared in Ukraine contributed to the two Maidans (Orange Revolution in 2004 and Euromaidan in 2014-Ed.).

In May 2015, we made a study that this group constituted about 10-15% of the population, mainly young people with higher education, residing in big cities. But, the majority of Ukrainians do not have such values. The question is which of these groups will prevail – the smaller active group that can move Ukraine forward and transform it, or the larger group that refuses change, is more traditional and conservative, and can throw Ukraine back a few decades. This question hasn’t been resolved for 25 years and we’re currently in the process of solving it, especially after the second Maidan. I have no definitive answers because they depend on many factors: the war, economic situation, etc. But, what is really important is that active group of young people, and there are many of them. Unfortunately, they have neither vision nor strategy.

O.L: Who should form this vision? Our leaders?

Y.H: Leaders should lead. There should be other people that can build a vision and open a direction for our country. There were no such plans in 1991, nor during the first Maidan, but such a strategy was discussed before the last Maidan in 2014. Today I see that more and more think tanks are being created, and that’s a sign of the times.

O.L: Let’s take the Nestor Group… I believe you’re a member. It’s not a think tank in the classic sense, but focuses on developing a vision for our country.

Y.H: We initially teamed up to create a vision for Lviv. The business community in Lviv asked us to look into it.

O.L: What about the Univ Group?

Y.H: Yes, it came first, in 2009. This is what entrepreneurs wanted: Help us do something so that our children don’t leave, so that they have a future in Lviv – because otherwise we’ll see our children once a year when they come to visit us, and our grandchildren will be speaking English or German.

We weren’t the only people thinking about Lviv’s development strategy; there were several parallel groups. Mayor Andriy Sadovy also started thinking about it and commissioned a monitoring survey. We worked in parallel, but the fact that two or three groups worked in parallel meant that there was a real need for this.

I personally believe that if something is going to happen in Ukraine then it must first happen in Lviv. Lviv was the first or one of the first cities to form a vision and strategy. Moreover, we think that we don’t have to govern the country or sell our product to some political party. We believe that the product should be so good that every political party would want to have it. But, then we realized that wasn’t enough. You can’t build a perfect city in an imperfect state. We then started creating a vision for Ukraine. Our main thesis is that Ukraine’s problem is not Yanukovych, but what will happen after Yanukovych.

O.L: Speaking of “what will happen after”, let’s take a look at populism. It’s gaining a lot of momentum and we often accuse politicians of being populist, but not the whole of society. How can we cure people of populist expectations?

Y.H: Populism is growing all over the world, and not just in Ukraine. The question here is how it manifests itself in Ukraine.

Populism, like corruption, can’t be avoided, but it can be kept under control like a wild animal in a zoo that we can point at. However, it’s one thing seeing the rise of populism in a rich country and another in a poor country like Ukraine. It’s dangerous here because we have all the disadvantages without the advantages. I believe there’s only one answer to populism – transformation, change, radical political and economic reforms. I’m not saying populism will disappear after that – probably not – but I hope that it will cause less damage.

O.L: You’ve mentioned radical reforms. But, Ukraine is in a very difficult situation – there’s a hybrid war, external conditions are deteriorating, we have yet to make a radical leap forward… If we lose these three years, will we be defeated?

Y.H: Countries such as Ukraine have their own path for development, and this must be a radical jump. This isn’t my idea, but the theory put forth by American economist Alexander Gerschenkron and confirmed by the Balcerowicz Plan in Poland in 1989. Economically and socially backward countries, such as Ukraine and Poland after the Soviet period, can’t overcome inertia through ordinary evolution. You can’t “grow into” social well-being; you can only “jump” into it. This jump is possible when there’s a window of opportunity – because of a crisis, major geopolitical changes or revolutions – when a new elite comes to power and has the political will to change the rules. My thesis is that Ukraine has had three opportunities, but has not seized any of them.

O.L: So what does that mean?

Y.H: Today, Ukraine has returned to its usual mode, slow and moderate changes, evolutionary and not revolutionary transformations. We’re returning to evolutionary change; we’re surviving and not living.

But, I don’t rule out new windows. They appear very suddenly. We’ve closed the window of opportunity, but a corridor of hope has appeared. For me, this corridor is linked to the new generation, which has a totally new set of values. It will inevitably grow older and will reach the age when by definition it wants to take power in our country. This corridor is tied to the next 20-25 years. It is important that these most active people do not become corrupt or leave the country in the next 20 years. These young people must come up with new political projects. This didn’t happen after the second Maidan – no new parties were born after the Revolution of Dignity. Perhaps it does take more time. But, it’s important that a logic of change and transformation is formed within this time, which will be part of most political programmes.

Man is basically lazy. If we could, we wouldn’t do anything. Crises drive change. A strong sense of crisis existed during the Orange government period when it became clear that the revolution had failed. Yanukovych’s rise to power was both symbolic and a consequence of this defeat. Euromaidan was different in that strategic changes were attempted before and during the revolutionary events. That’s when RPR, the Third Republic, and our Nestor Group appeared.

To make this strategy work, it should be adopted by everyone, and not just by some lone individuals or groups. The discourse must be changed. We call it differently – “spreading the virus”. We don’t need to join political parties, but we must spread this virus – specific terms and ideas, ways of thinking – which will become so widespread that no one will remember who said it first. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but a few new terms have appeared in Ukrainian discourse – sustainable development, open access, social contract. They’ve become very popular, but we were the first to launch these ideas. We were a little late with this virus, although it’s spreading quite fast today. I hope it’s irreversible… Unfortunately, more difficulties appeared after Euromaidan… we’re engaged in a long war, Europe’s going through a crisis, Trump reigns in America, etc.

O.L: Security is our weakest point. Ukraine is at a point of no return, or a kind of “moment of truth” in this conflict with Russia. Can our relationship with Russia evolve into something else? Will Ukraine experience new upheavals, as powerful and as important as Euromaidan?

Y.H: I’m one of those historians who believe that the real difference between Ukraine and Russia doesn’t lie in language or culture… in fact, they’re quite close. The main difference lies in our political traditions: versions of Putin, Stalin or Ivan the Terrible are almost impossible in Ukraine. A strong centralized government is also not possible because Ukraine has historically had a very strong organized society. Therefore, Russian history is written from the top downwards – a history of the state, while Ukrainian is written from the bottom upwards – a history of society. Author Anatoliy Striliany wrote a good piece on this topic. He pointed out that the Kozaky (Cossacks) flourished in Russia and Ukraine, but Russian history can be written without the Russian Cossacks, while Ukrainian history cannot ignore its Cossacks. The two Maidans and the war have contributed a lot to cutting the cord from Russia. This break will be complete only if we totally change the trajectory of political development and our political system, when we separate from the so-called “Russian World”.

If we manage to separate ourselves from this “Russian World”, then our success will raise the issue of Putin’s legitimacy and create an opportunity for another Russia. Therefore, Putin puts all his efforts towards making Ukraine fail. I must admit that our elite is sometimes unconsciously helping him… It’s really quite easy for him to say that Ukraine hasn’t chosen a viable path. Ukraine must separate from Russia politically, not only via its borders, but by implementing good reforms. Then, there’s hope for a new Russia, certainly not now because this war will last long. But, sooner or later I hope that Russia will change and we can live together peacefully. France and Germany were enemies for decades and are now working together.

O.L: You say that Ukraine is not Russia and give different historical explanations. But, what can you say about the fact that Ukraine is often associated with Russia?

Y.H: I’d like to refer to the words of a renowned Russian historian – Dmitry Furman. Before the first Maidan, he believed that Ukraine and Russia were very similar because they both have a kind of amorphous and underdeveloped society, a kind of huge fluffy amoeba without a backbone. Each “boss” that comes along can bend, kick, and beat it, but it survives; it can’t be destroyed because it’s an amoeba that comes running as soon as the “boss’ whistles. Furman changed his mind after the Maidan.

Ukraine is not spineless and will not be broken. This is a key phrase for me. And most importantly, this strong backbone can be found not only in Western Ukraine and in Kyiv, but also in the Eastern regions, in Dnipro and in other major cities.

O.L: You say Ukraine has a strong backbone… but if you take the 20th century and the complicated Soviet period, the two world wars, Holodomor, and Chernobyl, such a legacy has created a physically and spiritually “mutilated” nation. How can we transcend this legacy and move on while we’re going through a new war that will leave a deep mark on our society?

Y.H: Those events are distant in the past, by several generations. Ukraine’s greatest achievement lies in its new generation that doesn’t have this negative historical experience. It has grown up in conditions of relative democracy and prosperity. It can put an end to all these national defeats and disasters, which cannot be read without a dose of bromide (major medical sedative-Ed.), as Volodymyr Vynnychenko wrote. This is something that Germany was able to do. “Overcoming past history” is actually a German concept, but it has two different dimensions. You can overcome historical memory, come to terms with it by telling the truth about the Holodomor and the Holocaust,etc., but that’s a superficial solution.

The second dimension runs deeper – reforms that change the trajectory of history. It’s like an airplane that takes off and rises, but it must win over the gravitational force of history. Therefore, Ukraine should get rid of history per se, but that’s very difficult because on the one hand it’s helped Ukrainians to survive through a survival strategy. But, you should understand that survival is not like leading a normal life. Ukrainians can’t get out of this state of survival burdened by survival values and take on LIFE enhanced by values of self-expression. Some groups have managed, but not the bulk of our society. First, we must get rid of our society’s mental poverty, we must ensure its safety, and well obviously, we must be open to independent intellectual expert opinions.

O.L: In this context, what can we say about trust? So necessary, but sadly missing in Ukraine.

Y.H: Robert Putnam, an American political scientist, used Italy to illustrate the crucial role played by history in the life of a nation. Ukrainian history has all the elements and pieces that allow us to build institutional trust – the experience and example of ancient craft guilds, the Magdeburg Law, an autonomous church. So, we wouldn’t be building from scratch. Such positive history shouldn’t be overcome, but rather used, activated and multiplied.

O.L: Even if it’s so painful?

Y.H: Yes. You see, Ukraine has what it takes, but its potentials haven’t been articulated or discussed.

O.L: So, who should discuss them? People in general?

Y.H: No, not just any people… Society must put pressure on politicians, and intellectual leaders should articulate their thoughts. What we call the “intellectual elite”, which bears this responsibility and even gets money for doing this. But, I’m referring to the correct elite in the correct sense, the elite that has opportunities and responsibilities.

O.L: You’ve become an intellectual idol for many people. Who do you admire the most as an intellectual authority?

Y.H: I’d like to say just one word to people who consider me an idol. Don’t create idols for yourselves! The biggest challenge is to learn to use your own brain! Of course, the brain must be honed and sharpened, and you can’t do this without great examples and important texts. Personally, this man is Lubomyr Husar* in Ukraine, and elsewhere, the British historian Tony Judt, French philosopher Albert Camus, and Polish philosopher and historian Leszek Kolakowski.

*Major Archbishop Emeritus of the Ukrainian Catholic Church; resigned in 2011 due to ill health

O.L: Many researchers say that the line dividing the modern world was not between capitalism and communism, or between democracy and autocracy, but between open and closed society. How can anyone – the state or an individual – achieve a certain measure of success or live a normal balanced life in such a world?

Y.H: That’s a million dollar question! Nobody knows. We’re just getting to understand it. It’s a long discussion, but it’s important for Ukraine to take part in this debate and make its voice heard.

O.L: Lastly, a question about the Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU). It’s called an oasis, a high-quality, inspirational, and motivating place. You once called it a “child with great promise”. Where is this child now? Has it become a teenager?

Y.H: I think that child has grown up… People say that it takes a newly-created university 50 years to stand on both feet. The most important thing is that it was built on a good and solid foundation. I’m only worried about one thing – we’re growing too fast.

O.L: Your competitors – other universities – have experienced this…

Y.H: But we’re not competing! We don’t treat other universities as competitors. The question is whether we’ll be able to continue growing and still maintain our quality because, you know, the faster a teenager grows the more likely he is to have problems with his spinal column. Will our rapid development become sustainable? I hope that we can do it because we’ve built our institution on good solid principles.

Yaroslav Rushchyshyn, one of the organizers of the Granite Revolution**, now a successful businessman and an active community leader, once drew our attention to this matter. He’s also a philanthropist and member of the UCU Senate. He decided to support us when he attended a university meeting. Members of the administration were criticizing the rector, not maliciously, but as they say, constructively. Rushchyshyn then said: “I believe in you [UCU] because you know how to speak frankly and openly about your problems, while the rector sits quietly, listening and even provoking criticism in order to find weaknesses.”

We can talk about ourselves openly. If we can’t we’ll just disappear…

**On Oct 2, 1990, students launched a hunger strike and civil disobedience protests in support of labour strikes and their own demands concerning the Union Treaty (proposition by the Kremlin to strengthen ties among republics of the Soviet Union). The students occupied Maidan Nezlezhnosti, initially erecting about 50 tents.

O.L: Do you think the main problem is to determine whether the UCU is a university or a religious institution?

Y.H: No, that’s not the problem. Well, it is a problem, an inevitable one and even a positive one. After all, two good ideas can’t agree between themselves. But, by trying to unify two good things, you may spark a positive crisis, which can be a stepping stone for further development.

But, that’s not as important as our rapid growth, and we must be careful not to lose the quality of our education, staff and teaching. Ukraine has a big problem with quality education in higher educational institutions, so it’s easy for us to stand out among them.

We like to joke amongst ourselves …. The UCU will grow and prosper as long as things are so bad in Ukraine. But, the UCU is ready and willing to face difficulties when things get better in Ukraine.